Was she a Spy?

"I am not French," the woman told her accusers. "I have the right to have friends in other countries, even among those at war with France. I have remained neutral. I count upon the goodness of heart of you French officers." Thus Mata Hari summed up her defense before the court-martial in Paris on July 24, 1917. The three members of the panel retired to another room to consider a verdict. Within 10 minutes they were back. The international courtesan and self-styled Hindu dancer was to be shot as a spy.The tortuous road to the court room had begun 41 years earlier in the northern Dutch town of Leeuwarden, where a daughter was born to a tradesman named Adam Zelle and his wife on August 7, 1876. The girl was christened Margaretha Geertruida. At the age of 14, she was sent to a convent school to be trained in the domestic arts in preparation for marriage -the proper upbringing for young women of her class. But such a conventional life was not for Margaretha Geertruida. One month short of her 19th birthday, she married Campbell MacLeod, a Dutch army officer of Scottish origin who was 21 years her senior. It was a disastrous mistake.

In quick succession, the young Mrs. MacLeod gave birth to a son and a daughter and in 1897 accompanied her husband to the Dutch East Indies, where he had been given command of a battalion on the island of Java. MacLeod drank heavily, took up with other women, and beat his wife frequently once threatening her with a loaded revolver. Their son died under mysterious circumstances; according to one story, he was poisoned by a servant who had been mistreated by MacLeod. Shortly after the MacLeods returned to the Netherlands in 1902, Margaretha Geertruida separated from her husband (they were divorced four years later). Leaving her daughter with relatives, the young woman left for Paris and a startling new career.

Inventing Mata Hari

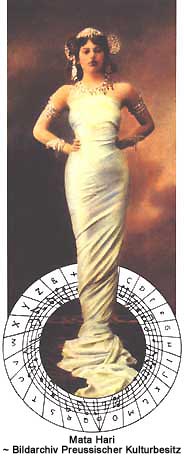

As a Dutch officer's wife and mother of two, Margaretha Geertruida would scarcely have taken the sophisticated French capital by storm. But as an exotic dancer from the East, she could attract the attention she craved. And so, by 1905, she had assumed a new identity, successfully passing herself off as the daughter of an East Indian temple dancer who had died in childbirth. To replace her mother, Margaretha Geertruida now claimed, she had been dedicated to the Hindu god Shiva and instructed in the erotic rituals of his worship. Tall and shapely, with blue-black hair, dark eyes, and a slightly brownish complexion, she was easily taken for an Indian. The exotic name she gave herself, Mata Hari, meant "eye of the dawn."

After a debut amidst the Oriental collections at the Musee Guimet, Mata Hari went on to score triumphs in Paris's elegant salons. She moved on to theaters in Monte Carlo, Berlin, Vienna, Sofia, Milan, and Madrid. All Europe, it seemed, was at her feet. Although members of her largely male audiences could claim that their reason for attending her performances was to

learn more about Eastern religions, they came principally to see a sensuous young woman who dared appear in public virtually nude.

Not surprisingly, the voluptuous dancer had scores of admirers who willingly paid for her generously bestowed favors. By the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, Mata Hari was said to be the highest paid courtesan in Europe. Among her conquests in Berlin: Germany's crown prince, the foreign minister, and the duke of Brunswick. On the day that war was declared, she was seen riding through the streets of the German capital with the chief of police.

Fateful Journeys

By the end of 1915 Mata Hari was back in Paris to rescue her personal belongings from her villa in suburban Neuilly, according to one story; to tend a wounded Russian lover, according to another. A third motive for the visit, espionage, was given in a cryptic message sent by the Italian secret service to their counterparts in France. The "theatrical celebrity named Mata Hari ... who purports to reveal secret Hindu dances which demand nudity," the Italians warned, had renounced her claim of Indian birth and was now speaking German with a slight Eastern accent.Detained by French authorities, Mata Hari vehemently denied being a German spy and impetuously offered her services as a secret agent to France. Curiously enough, the French accepted her offer and dispatched her to Germanoccupied Belgium with a list of six undercover agents there. Shortly afterward, one of them was captured and shot by the Germans - betrayed by a woman, it was said. Nonetheless, the French gave Mata Hari a new assignment: neutral Spain. She was to travel there via ship from the Netherlands.

The British forced the ship ashore at Falmouth on England's southern coast and arrested Mata Hari in the belief that she was a German spy named Clara Bendix. She gained her release by convincing the British that she was in the employment of France. Although advised by her captors to give up the dangerous role, she continued her journey to Madrid.

In the Spanish capital Mata Hari quickly formed liaisons with Germany's naval and military attaches, being paid generously for her services. What exactly was the nature of her services to the German officers remains the core of the mystery surrounding Mata Hari.

Invisible Ink for H-21

Toward the end of 1916 Berlin advised the two German attaches in Madrid that they were paying too much for the routine information being supplied by "Agent H-21"; send her back to Paris with a check payable by a French bank in the amount of 5,000 francs, they were ordered. The incriminating message was intercepted by the French secret service.On February 12, 1917, Mata Hari arrived back in Paris and registered at the elegant Hotel Plaza Athenee on the Avenue Montaigne. The next day she was arrested and charged with being a German double agent. The evidence used to sustain the charge was an uncashed check in the amount of 5,000 francs drawn on the bank specified in the German message and a tube containing what was identified as invisible ink - both seized from her hotel room.

The "invisible ink," Mata Hari explained during her interrogation, was a common disinfectant that she used as a contraceptive. As for the check, she readily admitted that it was a payment from the German attaches in Madrid - but for her sexual favors and certainly not for espionage activities. Unaware of her precarious situation, she made a number of ambiguous and unconvincing statements about her travels since the outbreak of war two and half years earlier. The former toast of Europe and mistress to men in high places was taken to the Saint-Lazare prison and assigned to cell 12. Among the room's previous inhabitants had been the female assassins of a former French president and a leading newspaper editor and Margueritte Francillard, who had been executed as a spy.

An Inconclusive Trial

After months of fruitless interrogations during which Mata Hari steadfastly maintained her innocence, the trial by court-martial was held on July 24, 1917. The president and two other members of the court were already convinced of her guilt - though crowds in the street waiting for the verdict maintained that she was innocent and hoped for an acquittal.Yes, she testified, she had viewed army maneuvers in Germany, Italy, and France -but as a guest of one or another of her many admirers. The 30,000 marks she had received from the German foreign minister? "That was the price of my favors. My lovers never offered me less." As for the 50,000 lives lost when French transports were torpedoed in the Mediterranean with information about sailings she had supplied, where was the evidence of such sinkings? The allegation was not backed up with any proof. Her use of the Dutch diplomatic pouch for messages from Paris? She was only writing to her daughter in the Netherlands. Despite the weakness of the prosecution's case, the guilty verdict was entirely predictable - given the temper of the times. The French high command desperately needed a scapegoat for the Allies' failure to break the three-year long stalemate with Germany.

Waiting for the Summons

The death sentence was not immediately carried out; and, during the ensuing months of waiting, Mata Hari grew increasingly nervous and despondent. The only night on which she slept soundly was Saturday, since executions were never held on Sundays. On every other night she went to bed knowing that a knock on the door at daybreak could summon her before the firing squad.An offer of her counsel to seek a stay of execution on the ground that she was pregnant by him was indignantly refused by Mata Hari. She preferred to place her hopes on a last-minute appeal for clemency to the French president. Her petition was denied. And thus, before dawn on Monday, October 15, she was awakened from a leaden sleep induced by the medication she had requested of the prison doctor. In a toneless voice her attorney told the convicted spy that she was to die that morning.

A Mock Execution?

Mindful of her reputation, the 41 -year-old woman took pains with her attire. She wore a pearl gray dress, a large straw hat, her best pair of shoes. About her shoulders she loosely arranged a coat. Only after she put on a pair of gloves was she ready to leave the prison cell for the trip by car to the Chateau Vincennes on the outskirts of the city.The firing squad was waiting on the rifle range at Vincennes, 12 men drawn up on three sides of a hollow square facing a tree stripped of its branches and leaves. With a firm step Mata Hari walked up to the tree. She accepted the shot of rum allowed a condemned person but refused to be tied firmly to the tree or accept a blindfold preferring to look her executioners in the eyes. As the rising sun pierced the night's fog, the priest and nuns attending her withdrew, the men of the firing squad drew to attention at the command of their leader, the signal was given. Twelve shots broke the silence, and the lifeless body of "Eye of the Dawn" slumped to the ground.

The reason for the condemned woman's exceptional composure at the moment of execution was later explained by a bizarre story. An ardent young admirer named Pierre de Morrisac arranged to bribe the firing squad into loading their rifles with blank cartridges. The execution was to be faked, as in Puccini's popular opera of the day Tosca. But like the operatic execution, the one in Morrisac's plot went astray; the rifles were loaded with real bullets - and the unsuspecting victim met a quick death.

The truth of this story - or of the one that Mata Hari flung open her coat at the moment of firing to reveal her nudity beneath to the soldiers? It is impossible to say and ultimately unimportant. Both tales are but part of the glamorous legend of the Dutch beauty who achieved fame in her lifetime as an exotic dancer and a high-priced courtesan - but who achieved immortality in death as the spy she probably never was.